INTELLIGENT, BRAVE HUNTERS

and a wonderful disposition…

all wrapped up in a black & tan "package"!

Frequently Asked Questions

All pups and dogs need a foundation of basic obedience as they head into the fun parts of field training. Commands such as “Come,” “Sit,” “Stay,” “Heel,” can be learned in any obedience class or taught by you (if you’ve done this before with other dogs), however getting a young dog into a formal obedience class has the added bonus of socializing the dog and teaching him to focus on you instead of all the distractions he’ll meet along the way. Later on, all those basic commands will be incorporated into your hunt training.

Meanwhile, if your dog or pup likes to carry a toy, dumbbell or dummy, go ahead and practice some retrieves. Some books suggest doing beginning retrieves in a hallway, so the dog has to come back to you rather than around. Having a long line on helps keeping him moving to you, rather than trying to lay down and chew on the toy. For starters, just keep this as a fun game, rather than requiring any formal deliveries. Quit before your dog gets bored with it.

As you start training in more open spaces such as a backyard or park, you’ll have your dog working farther away from you on a long training line. Many field trainers incorporate whistle training into their plans as they go along. You’ll use a dog whistle for this (not just whistling with your lips). Practices vary, here’s one way to do it: One long whistle means WHOA (more on that below), three long whistles mean COME, two long whistles mean change direction, and one short beep is a release whistle (meaning OK or GO!).

Even if your dog likes retrieving, most trainers would want to start with some "force breaking sessions," even though some trainers don't even use the term "force" breaking anymore. It's more like proofing your dog, meaning that he'll pick up and hold any object, even if he doesn't feel like it. This will come in very handy when he's asked to pick up a smelly duck, or if he's used to pheasant and flushes a chukar. Or maybe he’s just bored and doesn't want to do it anymore. Hunters insist that retrieving isn't an optional thing with their dogs.

Again, methods vary with this, but one time-tested method is ear-pinching. We’ll outline the basic process here. If you’re a beginner, you might be more comfortable seeking the guidance and supervision of a bird dog trainer with this step.

If a dog’s ears are sensitive, you'll be using very light pressure until he forces the issue. There's a definite progression in method, and most bird dog trainers use a training bench, an elevated long table-thing, so that when a dog resists, his backing up or twisting is more confined and controlled, but it can be done without the bench. If you don’t have a training bench and the dog wants to wiggle away, try sitting in a chair, with him leashed and sitting between your legs so that he can't scoot back or away from you. If you're right handed, hold the dog’s left ear gently with your left hand. You'll be on his right side, with your left arm reaching behind his neck so your hand has his ear. You aren't hurting him, and if he protests even this light touch, too bad. Insist that you have the right to hold his ear (just as you have the right to touch any part of him and cut his nails). You can rub his ear, talk to him, praise him, etc. Just don't allow him to pull his ear away from you. If he tries, use your thumb and index finger to press that ear. Keep pressing until he stops fighting you. Most dogs don't mind a light hand on their ear, but if your dog is a baby about anyone even touching his ear, he may need some time just getting used to the idea that its going to happen. Take as many sessions as necessary to get him okay with you holding his ear.

Next step: With your right hand, put a dummy in his mouth (2" wide canvas dummy probably better than larger or harder dummies). Hold his mouth shut on the dummy by pushing the bottom of his chin up so he can't spit the dummy out. You should be using commands like "Take It!" or "Fetch", "Hold", and finally when you let him open his mouth to release the dummy, say "Out" or "Give." Ask him to hold for just a few seconds at first. Just do this a few times, praising each time, then go play elsewhere.

The ear pinching comes in when a dog decides to spit out the dummy or not open his mouth to take it. The pinch on his ear gets his attention, he opens his mouth to protest, and in goes the dummy. As you insist on holding his mouth shut on that dummy, he might twist his head away, buck back, etc..., and the pinching continues until he stops resisting. Some dogs don't resist much at all, other dogs (like some Chessies and Airedales) will fight it more vigorously. But hang on. Pretty soon the dog realizes that when he stops struggling and holds that dummy quietly, the pressure on the ear stops. So he figures out how to turn it off. Once you get to that point, your dog should be holding a dummy without chomping on it with your hand under his chin for support for a decent amount of time -- let's say 30 seconds.

Next lesson: taking the dummy from you and holding it without you holding his mouth shut. Do as above with your left hand gently holding his left ear, your right hand offering the dummy. When you say Take it (or Fetch), he should voluntarily open his mouth for you to put the dummy in. If not, pinch the ear till the mouth opens, then in goes the dummy. Repeat until he's willing to open up voluntarily on the Take It command. Next ease up on the pressure with your right hand, which has been under his chin so that he couldn't drop the dummy. Your goal is to have him keep his mouth closed around the dummy, so just take your hand away for a few seconds, and if he starts to drop it, correct him with a Hold it command, hand back under chin, and ear pinch until he clamps his jaws tight around the dummy. Timing is the tricky thing here, since if he succeeds in spitting out the dummy, he's won. So make sure you bump his jaw shut before he gets that dummy out. Gradually he'll get the idea that he has to hold that dummy even when you aren't holding his mouth shut. You end the exercise by asking him to GIVE or OUT, and taking it out of his mouth. Do this in short sessions, and always end when he's done a better job than the time before. Gradually increase the time he's holding the dummy on his own.

Next, steps involve him reaching forward to take the dummy from your hand when you hold your hand a couple feet in front of him. Then he'll learn to take the dummy from your hand when you're moving alongside of him. Then he'll learn to pick up the dummy from the ground on the Take It command. And he'll learn to carry it while he walks with you, and then when he's called to you.

For an excellent discussion with photos of this process check out the classic training book, "Hup! Training Flushing Spaniels the American Way", by James E. Spencer. Spencer says you do two sessions a day – this should take you 3 to 5 weeks.

Next step, the dog will be given a dead bird (small chukar is good) to hold. The dead chukar gets tossed instead of the bumper and the dog gets to retrieve the bird to your hand. Since you probably don’t have access to dead chukar for training, this will also be done with the help of a local hunting dog trainer who can ease you into field work with birds, as well as fields where your dog can be trained off leash.

The next step some trainers like to do is to teach the "WHOA" command, which some trainers call "HUP!" That involves teaching the dog that isn't close to you to sit on a WHOA command, and alternately on one long whistle blast. Once a dog can do that, then you start throwing bumpers and making him WHOA (sit down) and wait till you release him before he retrieves them. This kind of training can start with the dog working at a distance from you on a long training line. Eventually, however, most trainers transition to an e-collar as the preferred training tool for reinforcing commands at a distance.

To digress a bit on training with e-collars: the e-collar's "nick" is adjustable so that you control how much stimulation your dog needs to choose to respond correctly to your command. You always start with a very low level, and only adjust upward if your dog is ignoring you. The e-collar should never be used to train an exercise. It should only be used when a dog clearly understands what he should be doing, and then he decides not to do it, so the collar "nick" is your long-distance tap on this shoulder to remind him he HAS to do it.

So for instance, your dog probably knows what "COME!" means, and he probably comes when he wants, and blows you off when there's something more interesting elsewhere. The e-collar will teach him that it’s always in his best interest to come when called. You give the dog a chance to come when you call or whistle. If he doesn't respond, then call again simultaneously with a collar correction. If he still doesn't come, the collar gets turned up. This may only happen when your dog is out chasing around in the field and decides he'd rather hunt independently rather than stay within reasonable (gunshot) radius of you. The more stimulating the environment, the handier the e-collar gets. The instant the dog turns off his independent path and starts heading back to you, you’re done with the collar button until he starts to deviate again.

For a new dog who has no idea what "come" means, stick with traditional treats, lures, long line, and happy praise. So teach your basic obedience exercises first, before re-enforcing with the e-collar. After the basics are understood, e-collars are also very useful for fine-tuning. For instance, an e-collar reminder can be more immediate and effective than a leash jerk or food lure for reinforcing off-leash heeling for dogs that like to move off ahead of you. Or the e-collar tap provides a reminder to the dog that likes to break a Stay when he decides he’s had enough. Many e-collars have a “vibrate” button that simply hums and reminds the dog to pay attention to you. Dogs soon learn that giving you the required response at the warning vibration avoids the stronger tap of the zap button.

Which takes us back to teach the WHOA command, that is getting your dog to sit on command when he’s at some distance from you. This translates into the "Sit to Flush" exercise in the field, in which the dog flushes a bird, but has to sit and wait while the hunter shoots it before he's released to retrieve it. Learning this is a good safety measure for the dog as it immobilizes him down in case a second shot is required to bring down the bird. Dogs that sit and watch the fall of the bird use that observation time head them to where it landed.

Throwing a dead bird instead of a bumper sounds grisly, but the dog learns to see the tossed bird "fly" through the air; he has to WHOA till released, then he gets to retrieve the bird to your hand. At this point, you might use the e-collar if the dog "forgets" to sit before retrieving, but don’t use the collar correction if the dog refuses to pick up the bird or to bring it back. Instead, go back to the lessons on Take It and Hold from force-breaking days, and use a long line to pull in a faster come back if the dog is fooling around instead of trotting right back.

Once the basics are done, then starts the introduction to the field. Having a trainer who has gadgets & birds to do this is very helpful, this is where your search for a local bird dog trainer pays off.

Many professional trainers start with homing pigeons in wire cages that can be released open with a remote control. The clueless dog goes into a field and hopefully catches scent of the pigeon and follows his nose. As the dog gets near the cage, the trainer triggers it open, the bird flies off, the dog is surprised, but he'll hear the long whistle and be told to WHOA. He is supposed to sit when the bird is "flushed" for him. All he has to do in these first lessons is find the bird with his nose and sit when the bird is released and flies off. Once the dog is released, he can try to chase the flying bird a little way if that gets him more excited about it. The e-collar to back up the COME command eventually is useful in bringing the dog back to you.

As the dog gets into this, he'll get the idea that there's birds out there and they're fun to find. At this point, the trainer puts out some planted chukar, and the dog gets to find and flush on his own. The next step is introducing shooting the bird. If you're pretty sure your dog isn't afraid of gunfire, the trainer will shoot a bird for your dog to retrieve. You'll be bursting with pride at this point.

If your dog has never heard gunfire, take the time to get him used to it gradually. One first step is to try the brown paper bag trick -- while he's playing or eating, have a helper stand fairly far away, blow up a lunch bag and pop it. That sounds rather like gunfire. If the dog ignores it, good. If he startles, you keep on playing or distracting him. Don't praise him for being scared (as in "it's all right, honey, you're a good boy"). Just pretend the sound isn't important. Some people use popper guns or starter pistols before exposing a dog to shotgun fire. Always begin making the sound effects from a considerable distance. Distant gunfire is far less intimidating than a gun going off right over a dog. Take some time making the transition from far-away loud bangs to those closer. Don’t rush your pup right to a gun club or hunt test field where shotguns are banging away all over the place – doing that can overwhelm a young dog who would normally be fine. Going slow and easy with gun noise acclimation can help you prevent a gun-shy dog later.

Once the dog does basic retrieves of a shot chukar, there’s a world of added exercises and steps. Line drills with dummies, retrieving bigger pheasants, water retrieves of ducks downed in water, and retrieving doubles. You might not see yourself as being this ambitious now, but as your dog’s enthusiasm drags you deeper and deeper into field work, you’ll find your own answer to the question “Why in the world would anyone not want to hunt with an Airedale?”.

Getting started, learning, training and more...

How about some tips on getting started in backyard training?

How do I find a good Airedale hunting pup?

By: Ed Weiss

The present classification of the Airedale places it in the small terrier group. But alas, the Airedale is not a small terrier, it is a hunting dog by history. Its classification and relative rarity has in recent decades masked the Airedale as a hunting breed. It’s development was for sport. This legendary English dog from Yorkshire was bred by sportsman for sportsman, crossing local hunting terrier foundation stock to larger non-terriers for the purpose of increasing hunting versatility. They were wildly successful.

This new sporting breed was molded in its formative years by selection based on success as hunter of vermin, water rats, and running rabbits to capture. As a result of the increased size, speed and scenting ability, non-typical-terrier pursuits as a retriever of waterfowl and field hunter flushing game birds were quickly added to its hunting quiver.

Even the early Yorkshire men could not imagine that their “Waterside Terrier” would be found in America hunting big and dangerous game. There appeared no limit to what this new breed could do. He was at this time, as they say, “hard bitten”. So it followed that his courage and ability to do whatever took him hunting lion with Teddy Roosevelt and serving as police and army dog.

Now it’s almost ninety years since these exploits, and the Airedale used as a hunter has to a large extent been replaced by his development as a companion dog and participant in non-hunting venues, such as obedience, agility, and conformation competition.

However there still burns in the breed embers of the hunting past, and if you are a seeker of adventure, the hunting Airedale can still be found!

The search will not be as effortless as seeking a pup from known hunting breeders of pointers, retrievers, hounds, or spaniels, since there are no longer well established breeders of Airedale hunting lines. There are however breeders that have produced individual dogs that compete well in hunt tests and are successfully used in the field in both water fowl retrieving and game bird hunting. Observing these Airedales, talking to their owners and breeders is a great place to start.

The Hunting Working Airedale association gathers the largest number of like-minded Airedale folk and their dogs at the annual September Hunting Working Nationals. Airedales can be seen in all their glory – from the young, to veterans – retrieving ducks, flushing game birds and tracking and baying raccoons. It is an event to fire up the imagination of what a pup from one of these dogs could become with training and a bit of luck.

Since observing a known hunting Airedale is not always possible, there are methods to improve your odds of finding your great pup, whether its parents hunt or not. To do this leads us into the very interesting study of canine drives and character and puppy evaluation.

Your pup is born with a personality and inborn desires and talents. They will be molded by experiences especially during its first eight weeks of life, but its behavioral foundation is immutable. These drives are the dog, and they would ensure its survival in a world without you. These “drives” are pre-programmed or inborn, and their strength will to a large extent determine your dog’s success in the field and attitude to its world!

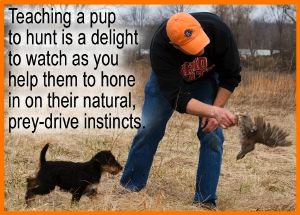

This fundamental drive is prey drive. It is the engine of the dog. The passion, the energy and lust for the chase is prey drive. The actions that manifest this drive are stalks, chases, catches and shakes. This is the preordained canine choreography of the hunt.

Prey drive is triggered by the stimulus of motion or scent. This burning inborn drive is the essence of the predator. This searching and pursuit is the embodiment of prey drive. It will be unleashed by the flapping of a bird’s wings, or the bounce of a tennis ball.

So how does one find this drive, or measure its intensity in a puppy?

First as with many puppy tests, it is ideally done at 7 to 8 weeks. The pup is taken to a quiet place away from mother and littermates. Then you (accompanied by a note taker, since you will be testing a number of prospects) begin.

The tester should hold a delectable fresh chicken bone at one end. Bring it down to the pups level with either crouching or sitting in a chair, and dangle it front of the pup. If the pup is hesitant make a few motions until it moves forward. Pup will have a wide range of responses from ignoring to chasing and biting it and then working the bone to the back of the mouth and not letting go with resistance. An in-between response is following the bone movement then coming forward and licking, or slightly grabbing it with the front of the mouth.

Another example of prey drive is ball drive. This is self- explanatory, but the ball is prey as it bounces and rolls away from the pup. As with all puppy tests, confidence, energy and enthusiasm should be observed and recorded.

Other pertinent aspects of character that will determine the dog you will have is seen in the puppy as degrees of hardness or softness. The “resilient animal” dog that responds without fear or avoidance to even noxious events is a hard rather than soft dog. Correcting this dog as part of training will not result in persistent cowering or avoidance. The distress of a correction, whether it is a collar jerk or the struggle of a game animal, is momentary!

Sound shyness to thunder or gunfire, or other loud disturbing sounds, is transitory and will learned to be ignored. Soft dogs become upset with loud noises, and that makes training difficult, as they are often sullen and withdrawn after a correction. They are not into the game of training.

How this all melds can be seen with a heeling lesson. The ball crazy prey monster will be focused on a ball held in the right hand while he heels on the left. If the heeling is incorrect, as by lagging or forging, a collar correction given to this dog does not end the activity with a sulk. The correction rather is followed quickly after the lagging has stopped by throwing the ball. The memory of correction for the hard dog gives way to a happy chase. For the low prey drive dog, the ball chase is not a significant reward. For the soft dog, the collar correction has thrown it into a sulk for which a ball or even a food treat may not sufficient.

In puppy testing, a sense of the pup’s hardness or softness can be evaluated by dropping a pail or cake tin on a hard surface near the pup being evaluated. In this test the genetic predisposition to sound shyness and fearful behavior can be sampled or unmasked. In an older dog genetic predisposition remains, but can be heightened by a history that includes lack of socialization or rarely abusive or traumatic encounters. Remember, the pup is the starting point of the dog. What you do when you take it home in the first few months will have a profound effect. Socialization is your next step.

Socialization of puppies is well covered in a pamphlet produced by one of our club members: “The Puppy Headstart Program” by Corally Burmaster.

A standardized approach to puppy testing is presented on the Volhard system website ( http://www.volhard.com/pages/pat.php ). In addition, a Hunting Instinct Evaluation is available annually through the HWA.

Good luck with your Airedale puppy selection! Pups are all different, but perhaps with a little effort and thought you will get the pup that becomes the all round hunting dog and companion you seek.

How do I start training my Airedale for field work?

It’s wonderful if your dog’s breeder actively selects his stock for hunting and is willing to be your mentor in getting started. There’s absolutely nothing better than a local mentor who’s willing to take you under his wing.

It would be nice to think you can learn to train your dog in your backyard and produce a working hunting dog, but that’s unrealistic for most people. You can do starting steps of basic obedience work and some fetching work with dumbbells, but sooner or later, you’ll need access to birds, fields with cover where a dog can run off-leash, and a gunner (if you don’t shoot). In other words, you’ll need some help.

If you don’t know of any local bird dog trainers, please scroll down to the “How do I find a local bird dog trainer?” section below.

Airedales are trained just like any hunting breed, so there's a ton of written information out there in books and publications like Gundog Magazine that will help you self-educate yourself. One highly recommended step-by-step book is Hup, Training Flushing Spaniels the American Way by James E. Spencer.

Another step that may take some getting used to on your part is the almost universal use of e-collars for hunting dogs. Before you reject the idea of an “e-collar” as “Oh, I’d never shock my dog,” do some reading and research on the proper use of the collar as an effective and humane tool to reinforce behaviors the dog has already learned. One classic (but pricey) book on the subject is Tritronics Retriever Training by Jim and Phyllis Dobbs. You can also find various training books and videos posted online –some better than others, but they at least show what others are doing.

So even though you might not find many people your area training hunting Airedales, you can be pretty sure of is that there are some people out there (everywhere) training hunting dogs, and if you can find them, you'll have a good chance of finding people to work with you and your Airedale. You may have to knock on more than a few doors, and some doors might not open to you, but use your terrier grit to keep on knocking, and you'll get there.

And... scroll down to the link on the left side of this page to learn more about how to start training for fur tracking.

How do I find a local

bird dog trainer?

If your Airedale didn’t come from a breeder who’s active in hunting sports, you’ll need to look around your area for other hunting enthusiasts who might help you. You may not find a lot of (or any) Airedale hunting activity in your area, so you might have to do what many of us have done – which is basically find someone who is training any kind of upland or retrieving breed and see if they'll work with you and your dog.

Use Google or another search engine to look up "hunting dog trainers." You'll find hundreds, but then narrow your search down to those relatively close to you by typing adding your state in your search. You probably want a trainer who will work with you to show you how to train your dog, so search for that rather than people who want you to board your dog with them while they train it for 6 months. The fun is in you working, training and learning together with your Airedale, so be willing to invest some time as well as money in working with a trainer who will teach you to train your dog.

You might find that you’ll follow up several leads that go nowhere, but don’t be discouraged. Be persistent – you’re an Airedale person! In addition to internet searches, ask anyone you know or even meet casually who owns a fit-looking sporting dog if they train their dog for field work. Many a good trainer has been recommended by word of mouth.

Also, use Google or other search engines to look up "hunting dog clubs" in your area. Many of our Airedale people have joined a local spaniel club or retriever club, and they find that making friends and training with the folks involved there is very helpful. It may be that this step is more helpful if you've done a little prior training so you come in with an Airedale who already has some skills to earn him some respect. It may be you’ll find a club whose members are just delighted to help a totally untrained dog of a non-traditional breed and its green owner, but more likely, the members of any dog club are mostly interested in working with their own dogs and enjoying the company of their peers. So if you approach a club with a dog that has some training, they may see it as not being out of place in their club. This gives you that chance to show them what an Airedale can do.

Another way to learn more about hunting dog sports and events is to check the AKC website, www.akc.org/events/search to see if there are any upcoming Spaniel Hunt Tests in your area. If so, you might want to go as a spectator. There may not be any Airedales entered, but you can see how the dogs work – and if you're the outgoing type, you can start conversations with owners and trainers, and perhaps find some folks who can work with you in your area.

Hunting, hunting supplies and equipment, and training dogs for hunting is a big business, though it’s so specialized that you won’t find it as prominently advertised as something more universal like pet grooming. But with some research and persistence, you should be able to find some experienced hunting people to help you work with your Airedale.

How do I train for a fur tracking test?

©2016 ~ Hunting Working Airedales, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Website created & maintained by Andrea Shaw

"Cava"– bred, owned and trained by Christie Williams – learns about flushing a bird at the HWA 2012 Field Nationals' while participating in the Flushing Workshop.